Ars Nova: The Music of the Fourteenth Century

In her book, A Distant Mirror, historian Barbara Tuchman dubbed the fourteenth century ‘the calamitous’. And in a political sense, this position is justifiable. It was during this period that Europe experienced some of her most far-reaching political and social upheavals: the black plague, the hundred years’ war, and the Papal Schism. And yet a focus on its calamities might blind the reader to some of its artistic triumphs. In literature, the fourteenth century opened rather gloriously with Dante’s Divine Comedy, and went on to give us Petrarch, Boccaccio and Chaucer. In the fine arts, it saw the frescoes of Giotto and Duccio, and the flourishing of the Sienese school. Finally in music, it produced the greatest flourishing of creative achievement seen in the West since the invention of notation.

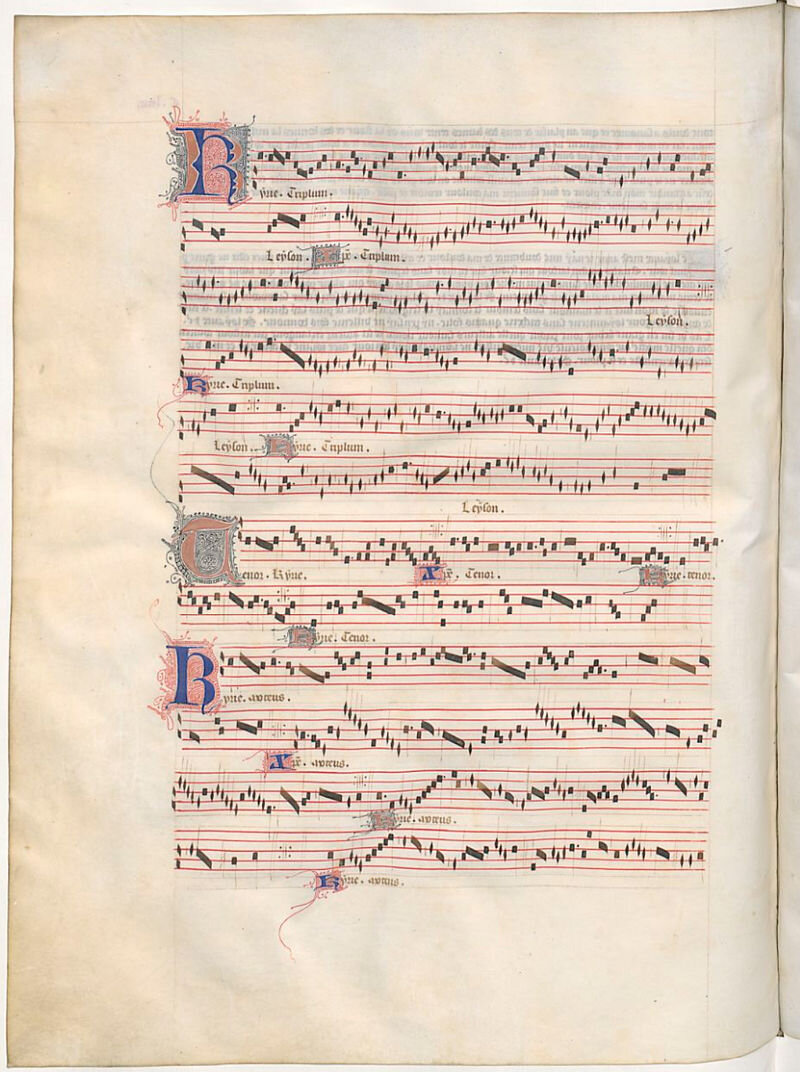

To music historians, the period is known by two appellations: the Ars Nova and the Trecento. The first refers to the musical innovations made in France during this period, particularly around the court of Avignon; the second, to the new wave of musical forms and styles sweeping through Italy during the same period. Though each has its own idiosyncrasies, which shall not be overlooked, I feel it is more helpful to consider them together, as two aspects of a unified musical movement.

There was significant transalpine cross-pollination, specifically in the south-easterly direction, and a high degree of parallel development, and so their differences, while not negligible, are outweighed by their similarities, which extend across most parameters of musical composition. Only in form and genre do Italian composers of this period, who displayed a penchant for the madrigal, ballata and caccia, differ significantly from their French motet-preferring cousins. In harmony, rhythm, counterpoint, and melody, there is much inter-relatedness.

Aesthetically, the musical fourteenth century stands out from its historical context in one important way. We note, in its major developments, a nascent humanistic bent that sees its literary equivalents, first, in the sonnets of Petrarch then, later, in the disquisitions of Mirandola. A certain confidence in man’s talent for wielding musical sounds and shaping them into complex aural forms begins to be noted on a unprecedented level. Where the high Medieval was self-defeatingly pious and deferent, subjugating his creative will entirely to god’s magnificence, the composer of the fourteenth century, while still undeniably reverent, begins slowly to toy with the idea of his own magnificence. Humbly, almost apologetically, he begins to put the stamp of his own ingenuity on his work, manipulating forms and sonorities, pushing envelopes harmonically and polyphonically,

It is no coincidence that the thirteen hundreds are known as the ‘age of the composer’. In previous epochs, ‘serious’ music – in this case, music for the liturgy – was composed anonymously. Chiefly, this meant one of two things: either that it was penned by a monk whose identity a historical bias against individual glory would conspire to keep unknown; or, that it emerged slowly and organically as a result of incremental contributions made by, not one, but many individuals over several generations.

Simply put, it didn’t matter who wrote the tunes, only whether they served their purpose well. And their purpose, unequivocally, was the glorification of the Christian deity. A person’s signature on a manuscript would have appeared irrelevant at best, and unforgivably hubristic at worst.

The first Western composers whose names are known to us are the twelfth-century Notre Dame orgánists, Pérotin and Léonin – although ‘known’, here, is a term best taken with caution. Scarcely any of the biographical information we have about these two murky figures is universally accepted as historical fact, not even their names.

Given the historical context, then, the fourteenth century appears remarkable indeed. The quantity of music that survives is exceptional, as are the dozens of names and surnames, birth and death dates that accompany it. Historical contentions of the ‘who-wrote-what-and-when’ variety still pop up, but they are no longer systematic. ‘Celebrity’ cases like that of Florentine Francesco Landini, renowned for his compositions and virtuosic organ playing, become more common. The creator of music is, for the first time in christian history, celebrated on his own terms, not merely as the conveyer of a divine message. His work is seen as worthy of being catalogued, documented and preserved.

And now for the music itself. What musical characteristics set the Ars Nova and Trecento apart from the preceding era? What aesthetic and stylistic advances give it the vaguely humanistic flavour Parisian organum, say, lacked?

Considered on the whole, the music of the fourteenth century can be seen as characterised by an unprecedented degree of adventurousness across. Seized by a sudden creative fervour, composers proved willing to take technical and stylistic risks, exploring avenues of expression that, to their medieval forbears, would have appeared alienatingly avantgarde. No longer bound to the liturgy as the primary paradigm of serious music making, the composer was free to venture into new territory, and so era saw a surge of secular genres: the motet in France, and the madrigal, ballata and caccia in Italy.

Across several technical parameters, the music of the fourteenth century would produce noteworthy innovations. The harmonic third and sixth, long considered ‘imperfect’ intervals, began to slowly creep into common musical parlance, as did leading tones, or sharpened seventh degrees of the scale. Polyphonic practice became more sophisticated, and rhythm is wielded for motivic unity. New forms were conceived to accommodate changing, humanising palates, and the West’s first largescale, multi-movement works begin to emerge.

Harmonically, the age would take its first vital step toward the formation of a fully-fledged diatonicism. In the hands of Ars Nova composers, vertical sonorities would slowly start to coalesce around thirds and sixths. In motets like Philippe de Vitry’s In Arboris, we see a stream of parallel thirds that would have appeared nothing short of cutting-edge at the time. His compatriot, Guillaume de Machaut features them prominently in his Messe de Nostre Dame, even in choral-style harmonic blocks and at sectional bookends. In Italy, Landini was enamoured of the third and, in ballate like Cara mie Donna, deploys them at every turn.

The use of thirds is far from uniform in the fourteenth century, to be sure. Some composers showed a greater predilection for them than others, and within the same composer’s output their preponderance can vary. Vitry for instance generally proved open to them, but his motet In nova fert is relatively third-poor and his Quoniam doesn’t feature them at all. And although there are notable exceptions, particularly Machaut, they are often called upon tentatively, only at phrasally unaccented moments, where they tend to cause least ruckus.

And yet the overall trend is clear: the third is coming to its own. The idea of its ancient prohibition, of its sonorous undesirability is, though not yet completely expunged, under considerable scrutiny. Where Pérotin would never have dreamed of the third as anything but a passing sonority on the same level as the second, Machaut, Vitry, da Bologna and Landini delight in sprinkling their works with it. Triadic harmonies tentatively emerge in Machaut’s Messe and many of the great Italian songs.

In the works of the Ars Nova greats, and to a large extent also in those of the Italian Trecento, the emerging third precipitates the concomitant evolution of the raised seventh scale degree. In his madrigal Fenice fù, Da Bologna felicitously couples the two, creating a sequence of parallel thirds that move to the tonic by means of a leading tone. In Appress’ un fiume (another Madrigal), da Bologna presents a leading tone but, cruelly, refuses to resolve it. In France, Vitry and Machaut manically littered their works with them. At times, their raised sevenths give the impression of a proto-perfect cadence, one without the fundamental. At others, a parallel leading tone, added to the fifth in a kind of ‘why-the-heck-not’ spirit, creates the distinctive and rather kinky ‘Lydian’ cadence.

The period is also characterised by greater-than-ever formal clarity, ambition and inventiveness. Composers like Landini ‘tightened’ musical forms, achieving structural tightness through the repetition of rhythmic and melodic patterns. Vitry invented the ‘isorhythm’ (or repeated rhythmic mode) to structure works like Quoniam. In new genres like the madrigal, we see the introduction of the first-ever tentative ternary forms. This was also the age of the West’s first large-scale work, Machaut’s Messe de Nostre Dame, a quasi-symphonic setting of the mass ordinary which, with its sprawling formal ambitions, abundant of use triads and bold polyphony, represents a clear qualitative leap over the much more ‘medieval’ Tournai Mass of a generation earlier.

The tone-smiths of the age also took a keen interest in polyphony. Rudimentary canonic features begin to emerge, such as those in Jacopo da Bologna’s Fenice fu and Landini’s madrigal, Musica son, where imitative passages are used colouristically. Caccias like Lorenzo da Firenze’s A poste messe and Giovanni da Cascia’s Con brachi assai are structurally canonic. In the latter, as well as in Gherardello da Firenze’s Tosto che l’alba, there is also a motet-style cantus firmus against which the two canonic voices are pitted. In Tosto, the polyphony of the interlocking canonic voices is especially tight.

In spite of its very real steps forward, the fourteenth century never quite shuffles off its medieval coil. Melodies are still in the theological vein: serpentine, amorphous and lacking any clear periodicity. Thirds are indeed used, but ‘shyly’, almost apologetically, and rarely at sectionally prominent junctures. Harmonic triads, though occasionally embraced for their rich sonority, never unequivocally point to an underlying circle-of-fifths structure. Chromatic insertions are ‘all-over-the shop’, having no clear logic or functionality. And the temptation to raise the seventh is given into, but leading tones behave erratically and don’t always resolve to the tonic.

And yet all the innovations discussed still hold. The music of the age doesn’t quite ‘get there’, but it tries. Though it never completely overturns the medieval paradigm, it boldly questions some of its presuppositions.

In many respects, the music of the fourteenth century is reflective of the metaphysical ‘in-betweenness’ of the age. In the works of its major composers, we note the same conflicting impulses to be found in the masterworks of Petrarch and Dante. On the one hand, there is the theistic devotion from whose grip no one is even close to breaking free; on the other, an increasing adoration for man, for his flaws and triumphs, for his genius and his suffering.