Pachelbel's Canon

MAGAZINE ARTICLE

In the following article, published by Limelight Magazine in September 2013, I discuss the lasting legacy and influence of one of Classical Music’s most enduringly popular pieces, Pachelbel’s Canon in D.

If you haven’t spent the last century locked up in a remote Himalayan monastery, you’re likely to be familiar with Pachelbel’s Canon in D. In fact, chances are you’re intimately – perhaps all too intimately – acquainted with it. Its use in wedding ceremonies rivals that of Wagner’s bridal march, and its instantly recognizable bass line has wormed its way into countless pop and rock tunes, making it well known even to those who otherwise dismiss classical music as the domain of chianti-loving serial killers. It’s regularly featured in cheesy relaxation compilations (admit it, you’ve got one), and any reputable Top 10 Greatest Ever Classical Music Hit List would almost certainly never fail to rate it. Yet ironically, the Canon’s astonishing appeal has also been its downfall. It’s been so mercilessly battered by decades of relentless overplaying, that it’s curdled into a vapid musical cliché, and its inclusion in any serious concert program nowadays would likely be greeted with supercilious side-glances and haughty scoffs. It’s spawned a plethora of arrangements, imitations, and quotations that range from the uncomfortably kitschy to the downright trashy. But what is the truth behind Pachelbel’s most famous creation? Why did nothing else Pachelbel wrote ever come close to rivaling the Canon’s great durability? And why oh why is it so damn catchy?

HISTORY’S FIRST ONE-HIT WONDER

Pachel-who? The Canon’s prominence in pop culture has led to a rather peculiar situation in which most people who have long internalised its repeated bass line don’t have the foggiest idea who penned it, nor what piece it hails from. Most who do know it as “Pachelbel’s Canon” will probably struggle to deconstruct the title semantically: “’Parkle Bells Cannon’? The ‘Bells’ part I can understand – it’s kind of musical. But, ‘Cannon’? Really, the piece doesn’t sound very explosive to me…” Among those select few, in turn, who know of Pachelbel, know that he was a composer and not a big, bronze resonator, and know the difference between a polyphonic form and a weapon of warfare, next to none would be able to name anything else he wrote.

Although scholarship is vague on his biographical details, by all accounts, Johann Pachelbel was highly respected and much in demand in seventeenth-century Germany, not only as a composer, but also as an organist and music teacher. It’s hard to imagine exactly how Pachelbel might have anticipated his legacy would fair posthumously, but we might suppose the poor fellow would have expected a little more than this. While most of his compositional output languishes in a mire of neglect, the Canon has soared to heights of unrivalled popularity and has suffered the inevitable indignities that come with uncurbed over-usage. We can almost hear Pachelbel’s indignant lament from beyond the grave: “Of all the hundreds of pieces I wrote, they remember only one? And that one? I mean – it’s just a silly repeated bass line! And, Gott, am I sick to death of hearing it! What about my beloved Hexachordum Apollonis? Couldn’t they play that instead for once?”

USAGE AND ABUSAGE

It may surprise be surprising (and, to some, refreshing) to learn that the Canon has not always been so celebrated. Originally paired with a Gigue, scored for quartet of strings, and named Canon and Gigue for 3 Violins and Basso Continuo, the exact circumstances of the Canon’s composition are unknown. What is clear, though, is that for centuries after the passing of its creator, the Canon lay forgotten on dusty bookshelves. Had it not been for a single surviving nineteenth-century manuscript now kept in the Berlin State Library, the work may have been lost forever. It’s unclear when exactly the Canon was rediscovered, but it was first published in 1919 and, in an inexplicable turn of fortune, over the course of just a few short decades thereafter, it went from being a piece that no one knew, to that piece everyone knew, whether they liked it or not. The Canon’s first recording took place in 1940 with conductor Arthur Fiedler at the helm of the Boston Pops Orchestra, and in 1970 French baroque specialist Jean-François Paillard presented what would become the definitive interpretation of the work. Where Fiedler had whizzed through the Canon in a hypercaffeinated flurry of barely discernible demi-semi quavers, Paillard took a more zen-inspired approach, slowing the tempo down by half and allowing the heart-breaking harmonic dissonances and contrapuntal melodic filigree to work their expressive magic.

Although it’s often been argued that Paillard’s recording is responsible for the Pachelbel revival, Canon Fever had by the late ‘60s already infected the masses, crossing over into that musical realm where it has exerted its most powerful influence: Pop. The precedent was set in 1966, when the Bee Gees released Spicks and Specks, a song built on a repeated bass line and harmonic structure almost identical to the Canon’s. Two years later, two European bands drew on bountiful reserves of kitsch to make neo-Baroque homages to Pachelbel: Greek pop outfit Aphrodite’s Child with Rain and Tears, and Spanish cool dudes Los Top Pops with Oh, Lord! Why, Lord? By the time of Ralph McTell’s 1969 wistful and nostalgic Streets of London, the Pachelbel bass line had gone well beyond a cliché to effectively become a standard pop music formula. Over the next few decades, the Canon would slowly extend the tentacles of its influence beyond the world of pop, reaching the work of a number rock, punk and even rap artists, including Aerosmith, Green Day, Blues Traveller and Coolio. No wonder comedian Rob Paravonian described Pachelbel as a terrorizing stalker who wouldn’t give him peace: “If he would just stay away from music that I love – but he won’t. He’s shameless. He will follow me to the ends of the Earth!” And Pachel-mania goes on to this day. As recently as 2005, Canon Rock, a grungy guitar version of the Canon by Taiwanese artist Jerry C was released, and has since reached an astonishing 16 million hits on YouTube. Aspiring rock stars everywhere take note: forget the eye-liner and penchant for hard drugs, all you need to become the idol of teens everywhere is the Pachelbel bass.

The key issue here is adaptability. The Canon possesses an extraordinary chameleon-like ability to reinvent itself for a variety of musical treatments. Take a moment to trawl through YouTube, and you’ll find a version of the Canon to fit all moods and musical proclivities. Wanna get in touch with your inner Bohemian? Try the Gypsy Canon. Gearing up for a night of fiery passion? Set the mood with a sultry Tango Canon. Need to unwind after a long day? Look no further than the Chill-out Canon with calming ocean sound effects. If you aren’t yet convinced of the Canon’s inexhaustible resourcefulness, listen to one of the following and you’ll get the message: the Smooth Jazz Canon, the Beatbox Canon, the Old Time Fiddle Canon, the Star Trek Canon, or Faerie Tale Canon (eh?). There are arrangements of the Canon for brass quintet, harp ensemble, a cappella vocals, glass harmonica, Japanese instruments, and even human whistles. To my disappointment, though, I never found a Pachelbel Canon for boomwhackers. All the same, this is a piece with a severe case of multiple personality disorder.

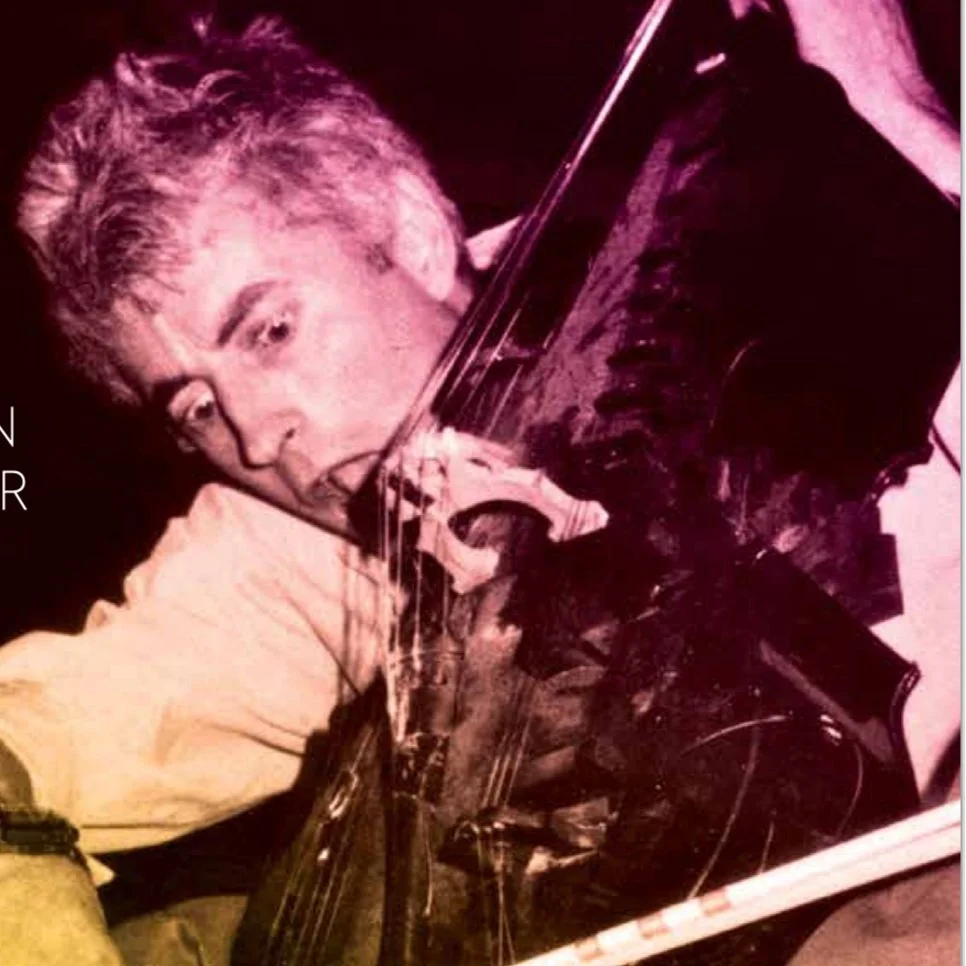

If it all appears a bit laughable, that’s because, well, it is. And comedians haven’t failed to cash in on the Canon’s absurd ubiquity to create biting satires of its annoyingly repetitive bass line. Paravonian dedicated an entire stand-up routine to the Canon, Pachelbel Rant, where he recollects the mind-numbing boredom he felt while playing the cello part in his high school orchestra: “I began to wonder, ‘Why would Pachelbel do that to [cellists]?’...And my theory was that he once dated a cellist, and she dissed him really bad”. Rambunctious Madrid-based vaudeville group PaGAGnini similarly tore into the Canon, using it as the basis of their début comedy sketch. “We couldn’t have chosen a more suitable piece,” says the group’s leader, violinist Ara Milikian. “It’s such a worn-out classical music cliché, and that bass part is so boring – we knew we could play with that.”

THE PERFECT EAR-WORM

So what about the Canon makes it so damn catchy? Are you ready to solve the Pachelbel puzzle? If you haven’t got it by now, you’re either still recovering from last night’s booze-up, or haven’t been able to tear yourself away from Candy Crush for long enough to concentrate properly. If you need it, here’s a hint: the answer is basic; or, rather, bassic. I’ll let English Baroque music guru Trevor Pinnock take over: “It’s that very simple bass line that captures the ear, repeated over and over again.” It’s as simple as that: repetition. According to a principle we might call the Philip Glass effect, we understand something more with every new time we hear it, and the more we understand it, the more likely we are to be moved by it (positively or negatively). And, as we know all too well by now, no one does repetition quite like Pachelbel. He uses an age-old renaissance technique, called ground bass, which, in this instance, manifests itself in two bars of eight crotchets (or notes a beat in length), and is repeated a total of 28 times. The ground bass provides the foundation over which the three treble voices play in canonic imitation, weaving their poignant filigree of ever-varying melodic ideas.

As important as it may be, repetition is a necessary, but not sufficient condition for a complete account of the Canon’s enduring charm. Pachelbel’s Chaconne in F also uses a ground bass, as do countless Chaconnes and Passacaglias written around that time. But why do we never hear the Chaconne in wedding ceremonies? And why has there never been a Chaconne Rap or Chaconne for whirlies and shakuhachi? The answer to this question is: contour. The Canon’s bass line may be simple, as Pinnock suggested, but it is not so simple that it completely lacks definition. The bass line has musical traits that set it apart from other, more mundane ground basses, giving it a distinctive shape and, thus, making it remarkably memorable. Firstly, the bass line’s intervallic structure is made up of a whopping 5 fourths: D-A, B-F#, G-D, D-G, A-D. Now, if your head is spinning a little, don’t worry. All you need to know is that the forth is a musical interval the human ear finds particularly easy to retain, so you can imagine how palatable a short musical passage will be if it contains 5 of these (the Canon may have met with quite a different fate, if Pachelbel had decided to build a bass line out of tritones!). Secondly, the Canon’s bass part contains a sequence, or musical material that is repeated at progressively lower pitches. The unit consisting of the first two notes is repeated twice, with the first repetition a minor second lower than the original, and the second repetition a major third lower than the first. Again, don’t worry if you’ve just had a brain hemorrhage. All you need to keep in mind is that your ear will find this sequence impossibly irresistible, and latch onto it without fail.

So there we have it. It turns out Pachelbel’s Canon in D is a perfectly engineered ear-worm, designed to wriggle its way into our ear drums and dig itself a permanent burrow in our memory banks. The mention of it in high-flying classical music circles may unleash a flurry of nose-thumbing and condescending gibes and, admittedly, it may not be an indisputable masterpiece, but the Canon’s intelligent construction, touching melodies, nobly nostalgic sentiment and, crucially, its ear-catching bass line have given it fame that extends well beyond the usual confines of its genre. If he had been alive today, Pachelbel may well have recoiled in disgust at some of the horrors his work has been subjected to, but he may also have been honoured and humbled by the countless tributes paid to it, directly and indirectly. After all, how furious could he be that half the world’s brides-to-be want to walk down the aisle to his heart-breaking sonorities, especially if the alternative for his life’s work would probably have been complete oblivion? Good ol’ Pachelbel could certainly have faired worse than being the Great-Granddaddy of one-hit wonders.

BREAK OUT BOX 1

Pachelbel: Myth and Reality

Accounts of the life of Johann Pachelbel are notoriously vague. Although the exact date of his birth is uncertain, we know he was baptised in Nuremberg, Southern Germany, on September 1, 1653. After studies under noted composer Heinrich Schwemmer and possibly also Georg Caspar Wecker, Pachelbel went on to hold posts in important German-speaking music centres such as Regensburg, Eisenach, Erfurt and Vienna. Since his death, hotshot music nerds like nineteenth-century musicologist Johann Mattheson have written with keen interest on Pachelbel’s life and achievements, and he has been credited as having brought the seventeenth-century South German organ tradition to its peak. Not surprisingly, no one knows for sure when or why he composed the famous Canon, although, fittingly, legend has it he penned it for a wedding ceremony. And not just any wedding: his close friend Johann Sebastian Bach’s!

But…wait a minute. We know Pachelbel and Bach’s older brother, Johann Christoph, were acquaintances. He even taught the elder Bach brother for a few years. But Pachelbel was a whopping 32 years older than Johann Sebastian, and there’s no real evidence to suggest the two ever interacted. Then there’s that pesky matter of chronology: Bach got married to his first wife Maria Barbara in 1707, a full year after Pachelbel died. Erhm, never mind.