Medieval Music: Ars Antiqua

The history of Medieval music is one of remarkable uniformity. From the earliest notations of the ninth century to the Ars Antiqua of the thirteenth, music in the West progressed at such a slow and reluctant pace, that the works dating from the end of this period are distinguishable from those at its beginning only by a few minor stylistic and technical advances, noteworthy more for historical than aesthetic reasons.

Throughout this half-millennium or so, the mainstays of medieval composition (the use of ecclesiastical modes, the supremacy of perfect consonances, and a lack of clear-cut melodic periodicity) remained largely unchanged. Up until the twelfth century, polyphonic practice – where it existed at all – was rudimentary. And even after advancements in musical notation made slightly more complex contrapuntal gestures possible, music in the Middle Ages remained, in all other compositional aspects, completely static.

Western music would have to wait until the Renaissance of the fifteenth century to truly come to its own. And though it may, at first, appear implausible that for 800 years Western music could have laid ‘dormant’ in this fashion, a careful consideration of the metaphysical backdrop against which it was composed will remove all skepticism – as we shall now see.

NEUMES

An exact telling of the story of Western music must begin, rather frustratingly, in the middle – at the point where the earliest forms of musical notation were invented. Before this, music in the West existed, of course, but its mode of transmission was exclusively oral. Since there was no system for writing it down, musicologists wanting now to understand it are faced with the impossible task of intuiting it from ancient musical treatises, like Boethius’ De Institutionae Musica, which offer no more than general theoretical descriptions of it. Any efforts to recreate it faithfully are, therefore, necessarily hypothetical.

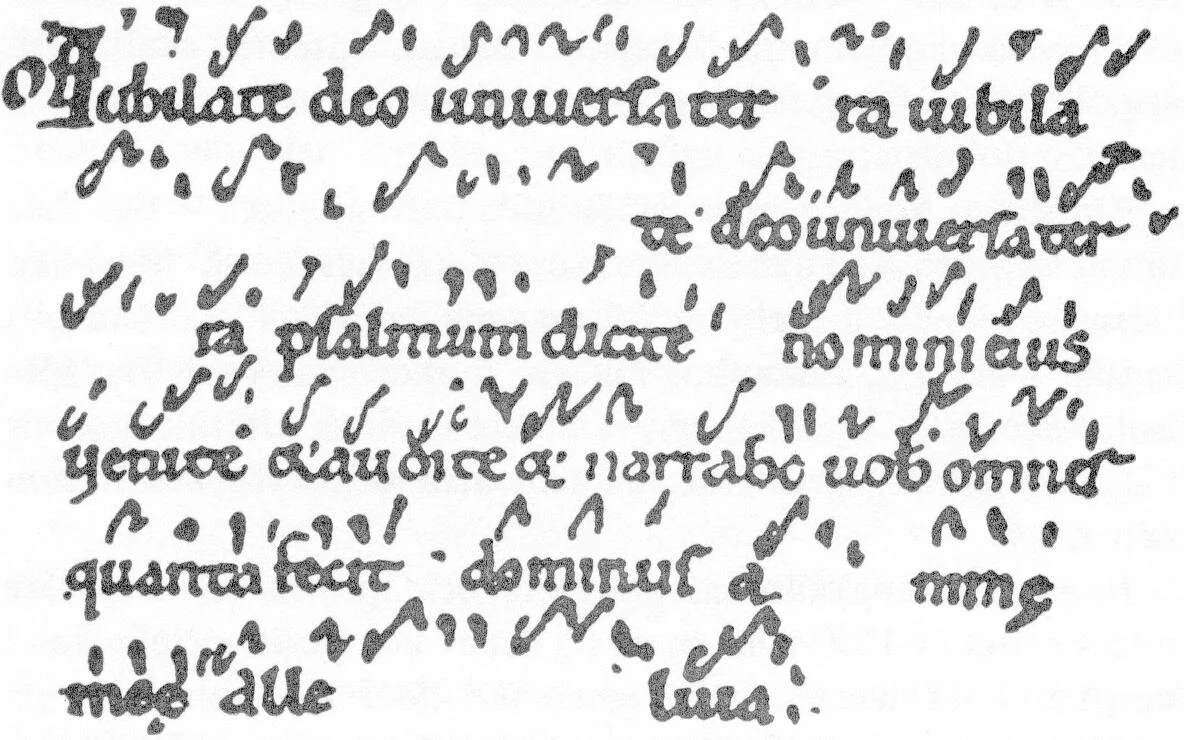

To complicate matters further, the evolution of notation itself was slow and stilted, and a reliable system for writing down pitches and rhythms did not appear in any mature form until well into the 1300s. For many centuries prior, notation was ‘neumatic’ - or consisting of characters called ‘neumes’ designed to give the musician an idea of the musical material at hand. Since neumes are often unheightened (they were not distributed vertically to show relative pitch) and staffless (there was no horizontal line, or ‘staff’, indicating absolute pitch), the musical data they yield is limited and inaccurate, obliging the contemporary scholar to fill the gaps with historically-informed conjecture. In the Middle Ages, their function would have likely been mnemonic; having already memorised much of the relevant music during rehearsals, the medieval singer would use neumatic notation merely to jog his memory, as a public speaker might use palm cards.

Early unheightened neumes

PLAINCHANT

As flawed as it may be, neumatic notation is responsible for having handed down to us that best-known of all genres of Medieval music: plainchant.

The origins of Western liturgical chant are, as many things medieval, steeped in a great deal of mystery. But there is reason to believe that Rome’s Schola Cantorum, the papal choir established by Pope Gregory I in the sixth century, may have played a hand in its early development.

It is under Gregory I that the earliest monophonic settings of the catholic liturgy are claimed to have been composed – although, since this was well before the advent of notation, it cannot be confirmed beyond a reasonable doubt. The first manuscripts purporting to document old Roman chants date to the 11th century – a full half millennium after their alleged conception. During this lengthy period, they were transmitted orally, and one can only guess at how faithfully they were preserved.

When the earliest neumes emerged in the ninth century, various plainchant traditions had existed for some time, each with its own distinct melodic features. By the eleventh centuries, most of these were supplanted by the Gregorian rite, which itself was something of a hybrid, having evolved slowly during the eighth century when Frankish kings began to introduce Roman chant in the Carolingian kingdom.

After a long period of assimilation, a new style of plainchant emerged, which, according musicologist Richard Taruskin at least, might more accurately be called “Romano-Frankish” than Gregorian, as it’s currently known. However you call it, there’s no denying its historical importance; Gregorian chant would remain the Western World’s dominant form of sacred music-making for four centuries – until the slow emergence of complex polyphony.

A cursory glance over this ‘golden age’ of plainchant will attest to a fact we’ve already mentioned: that, minor idiosyncrasies aside, the sacred music of this era is, aesthetically, remarkably uniform – both across time and space. Sure, the chants of the Roman rite were marginally more ornate than those of their Gregorian counterpart; and yes, the Frankish tradition included peculiar subgenres, like tropes and sequences, that others – like the Gallic, Ambrosian and Beneventan – seem to have lacked. But the differences are almost imperceptible, and amount to little in the face of the overwhelming commonalities that bind them.

These can be summarized as follows:

Monophony: Throughout this entire period, plainchant textures remained resolutely monophonic, and this is perhaps its defining feature. The first hints of complex polyphony would not be seen until the Notre Dame School of the twelfth century. Earlier polyphony is documented, it is true, but it was so rudimentary that it can hardly be deemed worthy of being called so. And without polyphony, there could, needless to say, be no functional harmony. The towering harmonic system based on the circle of fifths, which would come to characterize all western diatonic during the Common Practice Period, would therefore have to wait until the high Renaissance to emerge.

Textual melodies: The general architecture of chant melodies followed the same basic principle throughout this period. They were composed to serve the Mass, and so they were composed to fit the liturgical text and drew to an end when it did. Since their structure was dictated primarily by linguistic rather than musical considerations, they lack the periodic form you find in melodies of the enlightenment or in the pop tunes of our day, and they might, to us, seem to meander aimlessly, without any apparent internal logic. Because their architecture lacks conventional melodic building blocks (called ‘phrases’), we might find ourselves guessing, at any given point, whether we are still at the chant’s beginning, toward its middle, or nearing its end.

Modes: The use of the ecclesiastical modes remained constant. These were ways of organizing pitch collections into various orderings of tones and semitones – what we would today call ‘scales’. The medieval modes were eight in number, and were organized along the white keys of the modern-day piano, with each mode beginning on a different degree of the C major scale. Throughout this period, the composer never ventured beyond them, not even timidly. And there were, admittedly, superficial musical reasons for this: since each mode yielded its own unique ‘affect’, and also because the medieval had no harmonic use for it, there was deemed to be little necessity for chromatic variation – or use of the notes corresponding to the black piano keys – for delight and spice, and so the melodies of this era remain thoroughly (and one could argue blandly) diatonic. But there are deeper reasons at work, as we shall now see.

MUSICAL THEISM

To our ears, medieval chant sounds remote and alien. Serpentine melodies meander along aimless trajectories. Cold melismatic figures seem to hang in suspended animation, and offer the soul no comfort from the world’s bleakness. And yet the medieval aesthetic is firmly of its time; a musical language perfectly suited to the metaphysic of which it was a product.

According to the prevailing worldview, God was supreme and man, flawed. God’s truth was one, immutable and eternal, and our faculties of reason, since they were fundamentally limited, permitted us to see but a slither of it – and even then only if god deigned to grant it. Since Adam’s fall, we’d been inherently wicked, burdened by original sin and ever susceptible to the temptations of the flesh. The only way out of our wretched lot was through the redemption of Christ, who was the light and the way; the Christian update of the ancient Greek Logos concept.

Against the backdrop of such a god-oriented metaphysic, it is hardly surprising that the musical aesthetic which developed was one that shunned aesthetic innovation. This was a firmly theistic paradigm; any stylistic indulgences betraying so much as a hint of humanistic hubris were unacceptable. This was an art that dared not draw attention to itself. Creative energy had to be wielded, not for the exultation of artistic genius, but for the glorification of god. Stylistic frills were, at best, unnecessary and, at worst, sacrilegious. They were the unpardonable intrusions of man’s wicked ego, potentially dangerous distractions from his duty to worship the creator.

The ecclesiastical modes and monophonic sparsity were kept as they were – simple and solemn – because they served their purpose better than any other conceivable compositional devices: they reflected the indivisibility of divine truth and the ineffable simplicity of god’s essence. Stylistic innovation would have required a humanistic drive to originality, which might have generated theological disapproval, and was occasionally met with Church censorship, as at the Synod of Meaux of 845.

Once the chant had reached its zenith, it remained static because the metaphysical concepts that had given rise to it also remained constant. It would take the humanistic shift of the Renaissance to break this aesthetic straight jacket, and that wouldn’t happen for another 300 years.

EARLY POLYPHONY

Polyphony evolved slowly in the West, beginning with the earliest tentative forays in the ninth century and reaching its zenith with the Baroque masterworks of the eighteenth.

Essentially, polyphony is the practice of composing music that involves two or more melodically independent voices sounding at the same time. Western music has cultivated this craft steadily for 1,200 years and, in this sense, it is unique among world music traditions. Other musical cultures that compose polyphonically tend to keep their contrapuntal textures relatively simple; either by ensuring additional voices are rhythmically unisonous with the melody or by slowing accompanying voices down so that they move only at harmonically and melodically pivotal points.

For centuries, Western polyphonic practice lingered in a comparably early developmental stage. Where early polyphony is documented – in such treatises as the Musica Enchiriadis (ca. 850) and Guido d’Arezzo’s Micrologus (ca. 1030) – they are depicted, without exception, as extremely rudimentary, and might better be called note-against-note doublings at the fourth, fifth and octave, than voices fully independent from the cantus, or original chant voice.

But this would slowly change. During a period that later generations would name Ars Antiqua (or ‘Ancient art’), the first small but vital steps toward modern polyphony would be taken.

The Ars Antiqua style refers specifically to the pioneering contributions to polyphonic music made by two men working at the cathedral of Notre Dame in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries: Léonin and Pérotin. As we shall see shortly, these two composers would take polyphonic composition to unprecedented levels of complexity. But before we discuss the innovations ushered in by the Notre Dame school, it is first necessary to speak briefly of an earlier development in musical notation that made them possible.

Guidonian staffed notation (12th century)

THE STAFF

At the turn of the eleventh century, a remarkable array of notational systems existed in Western Europe, possibly as many as there were styles of plainchant for which they were conceived. They differed from one another in subtle details, but all were alike in one important way: they offered no means of clearly indicating relative and absolute pitch. As we have seen, this meant that singers using early neumatic scores could rely on them merely as memory aids, rather than accurate notational representations.

Wanting to at least partly rectify this, the eleventh century monk, Guido d’Arezzo, would make an innovation that every subsequent generation of musicians has thanked him for: the staff. A single line drawn horizontally, representing either the note F (if the line was red) or C (yellow), would turn out to be critical historically far beyond this humble monk’s wildest imaginings. Where all Guido intended was to create a visual aid for the identification of absolute pitch, what grew from this rather simple idea amounts to nothing less than the entire edifice of Western Classical Music – although, admittedly, it would take a few centuries before the enormity of Guido’s ingenious invention truly made itself known.

NOTRE DAME ORGANUM

Let us now return to Léonin and Pérotin in the twelfth century. Armed with new advancements in musical notation, which by this time included, not only Guido’s staff (now increased to five lines), but also square noteheads for even greater rhythmic precision, the Notre Dame polyphonists could claim unprecedented compositional freedom. Singers could suddenly rely almost completely on their scores, which now accurately represented pitches, and so had little need to memorise their music. Liberated from the restrictions of our limited capacity for memorisation, composers could now experiment with bold new textures which, in the days of neumatic notation, would have been impossible.

The ‘breakthrough’ came with the realisation that, with staff notation, one could compose many notes against one. If the cantus firmus (or the chant voice) was slowed down, other voices could be overlaid above it, providing a polyphonic filigree against the original tenor. And this is precisely how Notre Dame Organum evolved: clausulae (or sections of older chants intended for soloists) were excised for polyphonic purposes, and ‘organal’ voices were added. These would sing in long, melismatic gestures over the cantus, while the latter stayed in a fixed position. Able to rely more or less fully on his score, the cantus singer could now tell precisely at which point in the music he needed to move to the next chant note, and the organal voices were able to sing ever longer and more sinuous melodic figures.

Little is known about Léonin and Pérotin. Outside an anonymous thirteenth-century treatise, there is no mention of Pérotin anywhere and, although several historical figures have been proposed as likely candidates for Léonin, none matches him conclusively. Be that as it may, two pieces attributed to them have survived, and stand as a testament to the polyphonic achievements of the Notre Dame school. Since they both set the same psalm to music, they known by the same name: Viderunt Omnes.

Léonin’s Viderunt and Perotin’s differ in a fundamental way: where the former was written for one organal voice against the cantus, the second has two additional voices for a total of four: three organal voices against the cantus. Pérotin’s organum quadruplum is, for this reason, historically more important. The additional two voices create challenges of polyphonic coordination for which Pérotin had to find creative solutions. These set stylistic precedents that would be applied and developed by the next generation of composers.

Staying in step with the older polyphonic practices of the Musica Enchiriadis, Pérotin organised his vertical structures around intervals of the fourth, the fifth and the octave, never allowing the melody to come to either a phrasal or a sectional rest at any other interval. These three organal verticalities would, in circa 1240, become known as ‘perfect’ consonances, and the pure, Pythagorean harmony – the symphoniae – they generated, would inform the polyphonic language of the remainder of the middle ages.

Pérotin’s organum would also have a critical influence on the secular music of the next century. In certain sections of Pérotin’s work, the cantus speeds up, almost matching the rhythm of the three organal voices. These livelier passages, known as discantus, proved particularly interesting to the early pioneers of the motet, who, simply by substituting poetic text for the organal melismas, effectively create a new genre.

Léonin: Viderunt Omnes

The polyphonic developments spearheaded by the Ars Antiqua have been much lauded by musicologists. And rightly so, for their impact was indeed revolutionary. But the revolution was long drawn out, for their latent aesthetic potential would not be realised until the fifteenth century. Until then, the medieval theistic outlook kept a stranglehold, more or less absolute, on all artistic forms of expression, and the prevailing aesthetic remained by and large unchanged. Ecclesiastical modes and unperiodised melodic forms continued to hold supremacy. Polyphony would remain, for a long time, as it had been laid out by Pérotin: organized around perfect consonances. All in all, musical expression would remain god-focused, if not outwardly in content, then certainly inwardly in aesthetic, until humanity’s gaze began, boldly, to shift from the heavens back to terra firma. The greatest and farthest-reaching musical revolutions, those that truly ushered in the modern musical era – triadic harmonies, chromaticism, ternary forms, periodized melodies and, most important, common practice tonality based on the circle of fifths – were yet to come. These would have to wait for the humanistic shift of the Renaissance.